The Jersey Nano-Brewery Roundup

For something that by definition means very small, they've become big in craft beer.

For something that by definition means very small, they've become big in craft beer.

And the Garden State.

Nano-breweries, sized 2 barrels and smaller, if you need a general definition, have been popping up across the country like dandelions in spring. The unofficial coast-to-coast count is nearly 60 now making beer and 40-plus in development.

In New Jersey, they're a big part of those itching to enter the brewing industry. Half of the 10 craft brewing projects to emerge over the past 12 months have been nanos. Of those, one has started brewing; another is on the cusp of striking a mash.

Great Blue Brewing at Suydam Farms in Somerset County, licensed on Feb. 28, christened its 2-barrel setup with a red ale. Deep in South Jersey, down the shore, is where Cape May Brewing installed a one-third barrel rig that federal regulators signed off on April 1. Cape May Brewing's state approval is expected soon. But wait, there's more.

But wait, there's more.

Flounder Brewing is settling into leased space in an industrial park building in Hillsborough to become a 1.5-barrel brewery; in Ocean County, homebrewers calling themselves the Jersey Shore Brewing Experience are shopping to bar owners the idea of installing a 2-barrel brewery. The intended result: a brewpub via the nano track.

Meanwhile, Pinelands Brewing, the handle taken by a homebrewing duo in Atlantic County, has set its sights on a building in Egg Harbor City, the former host town of Cedar Creek, a now-defunct brewpub that made beer in the mid-1990s. Its 2-barrel system is now used at Great Blue.

The buzz about über-small, commercial brewing isn't lost on the trade group that represents most of New Jersey's craft brewers. "We'll welcome anybody that makes craft beer in New Jersey into the guild. That's always been the case," says Trap Rock brewpub's Charlie Schroeder, vice president of the Garden State Craft Brewers Guild.

By all accounts, the nano wave is the result of ambitious brewers – many of them rather accomplished homebrewers – looking to put their beers in front of someone besides their friends. They want to go pro, and they see nanos as an affordable foot in the door of the burgeoning craft beer industry. It's an entry point that steers around taking on the steeper expense of 10-, 15- or 20-barrel brewhouses and accompanying tank space.

With nanos, you can hang onto a day job that you're not financially ready to leave; yet you can still brew commercially and try to carve out local markets for beers that range from session strength to imperial. Nanos may be baby steps, but for some of the folks behind them, the vision includes going big someday.

"It's an effective way to enter the business, enter a market and build a brand," says Flounder Brewing's Jeremy Lees, a senior sales manager for a North Jersey manufacturer. Flounder (yes, the name's an Animal House reference) is a family affair that includes Jeremy's brothers, Mike and Dan; his brother-in-law, Greg Banacki Jr.; and cousin William Jordan V. "A nano lets us do this while dealing with responsibilities we now have. I do hope one day my full-time job is to be brewing beer. But you can't have a full-time job brewing beer as a nano brewery."

Paul Gatza, director of the Colorado-based Brewers Association, the craft beer industry's trade group, says nanos started showing up on the association's radar around 2008. "I think the movement of homebrewers into more sophisticated brewing systems and the availability of those systems are definite factors in pushing nanos forward," he says.

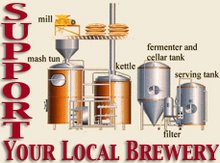

Those more sophisticated systems are what companies like Sabco, Blichmann and Psycho Brew are all about. They're the bridge between homebrewers and craft brew start-ups that jumped into the game on the larger scale.

Chris Breimayer and his brother, Pat, are the people behind the year-old Psycho Brew in Belding, Mich. Breimayer, an architect/engineer and homebrewer, turned to making custom brewing rigs after the slowdown in the housing industry.

Psycho Brew has sold a dozen systems – nearly all of them to nanos in development – since the fall, when Breimayer placed an ad on ProBrewer. Psycho Brew's biggest system runs about $13,300 and can produce 3 or 4 barrels. Breimayer spends a couple of hours each morning working out price quotes for prospective buyers.

"A lot of poeple don't have the money for the bigger systems. They can buy ours and prove their prowess and then step up," he says. Nanos that eventually outgrow their Psycho Brew rig can still use them as pilot systems for recipe formulation. (Psycho Brew is putting together a pilot brewing system for Brewery Ommegang, by the way.)

Keeping tabs on nano-brewers across the country is a side interest of Mike Hess, whose eponymous 1.6-barrel nano-brewery in San Diego started making beer last July. One of San Diego's 37 licensed breweries, Hess Brewing was expected to hit a total production mark of 70 barrels by the end of last month. (Hess features among its brews an 11% ABV pale ale and a rye imperial stout that's just under 10% ABV.)

Mike's blog, the Hess Brewing Odyssey, chronicles the nano niche and has become the de facto guide on starting a nano-brewery. The Brewers Association even steers folks interested in nanos to the Odyssey. Under the heading The Great Nanobrewery List: From CA to MA, Mike keeps a running coast-to-coast count on nanos that are operating or are in planning stages.

"I get email twice a week with something to add to the list. It gets updated as often as we get new information. We've done our best to keep it as thorough as possible," says Mike, who also owns a financial services business and has homebrewed since 1995.

The current count: 57 brewing, 42 on the drawing boards.

Andy Crouch, author of Great American Craft Beer and keeper of BeerScribe.com, finds a contrast between nanos and some brewing enterprises tripped up by a past industry shakeout. The people behind nanos have more beer savvy and are driven by something more pure of heart than those past entrepreneurs who envisioned a payday in microbrewing.

"They didn't really know about beer, know about distribution. They were just in it because they thought it was a good fad or a trend, and they just wanted to make some money. A lot of them lost a lot of money," he says. "These days a lot of the growth we're seeing is, oddly enough, in the opposite direction, people who aren't necessarily in it for money; they're in it to make very small batches, these nanobreweries. Here in New England, where I live, there are probably at least 10 that have opened up in the last two or three years, making 1- to 2-barrel batches."

These days the Garden State is witnessing the biggest surge in brewery or beer company development in more than a decade.

In 2009, the well-established Iron Hill brewpub chain opened its eighth location – but its first in New Jersey (Maple Shade). Last year, production brewer New Jersey Beer Company (North Bergen) launched, as did Port 44 Brew Pub (Newark) and East Coast Beer Company (Point Pleasant in Ocean County), a contract-brewed label. Turtle Stone Brewing (Vineland, Cumberland County), an enterprise in development from late 2009 and through last year, was still looking for a site while warehousing brewing equipment (a brewhouse from a shuttered Rock Bottom brewpub and some 15-barrel fermenters).

By the start of 2011, seven more projects were in development: production brewers Kane Brewing and Carton Brewing (both are located in Monmouth County and have licensing paperwork pending with the state) and nanos Great Blue; Cape May; Flounder; Pinelands and Jersey Shore Brewing.

Great Blue entered the state's craft beer scene with a concept to use hops grown at Suydam Farms in its beers targeted for bars and restaurants near the farm. The owners say they still have some bugs to work out on their brewing system, but they plan to put it in service a second time later this month. Cape May Brewing hopes to be making beer in time to hit the summer season and build a following throughout the shore region. A tiny one-third-barrel system was installed in their building in Lower Township to secure approvals from federal and state regulators. Plans call for upgrading as quickly as the brewery's market will allow.

Cape May Brewing hopes to be making beer in time to hit the summer season and build a following throughout the shore region. A tiny one-third-barrel system was installed in their building in Lower Township to secure approvals from federal and state regulators. Plans call for upgrading as quickly as the brewery's market will allow.

Flounder Brewing hopes to be making test batches of beer by summer and launch the brand with a bottled Hill Street Honey, an American amber ale made with honey from a New Jersey farm. "My grandfather was a beekeeper, he was the original artisan in the family," Jeremy says.

The guys at Flounder hope the market lets them grow to 2 barrels quickly. "To start we would be doing 20 gallons at a time, two cycles being 40 gallons a brew session, so about 1.5 barrels per brew day," Jeremy says.

Bottling will be handled on a counter-pressure filler like some brewpubs use to fill growlers (his model is an older version of the kind in use at Iron Hill). If their market takes off, he says, they may contract out some brewing and offer draft beer.

For now, Jeremy says, the brewery's tour/tasting room has been finished; an architect was hired recently to do utility work design for the brewery buildout. Farther south, in Ocean County, Wayne Hendrickson and three homebrewing colleagues in Bayville have been pitching nano-brewing to bar owners, hoping one will take them up on the idea to invest in a restricted brewers license and let them install a 2-barrel system to turn the tavern into a brewpub.

Farther south, in Ocean County, Wayne Hendrickson and three homebrewing colleagues in Bayville have been pitching nano-brewing to bar owners, hoping one will take them up on the idea to invest in a restricted brewers license and let them install a 2-barrel system to turn the tavern into a brewpub.

Their sales kit consists of a white four-pack carton of sample beers: Screamin' Demon English Red, Gütesbier German Alt, Trouble Maker American Ale and XPA Extra Pale Ale.

Their company name comes partly from the sense of community that craft beer creates.

"We're all Jersey Shore guys," Wayne says. "We wanted it to say a little more. It's more than the beer; it's about the (beer) experience."

After months of making their pitch, Wayne says they may have a bite, someone who's interested in buying a bar and adding a small brewery. Jason Chapman of Hammonton (Atlantic County) says he unsuccessfully made similar pitches to bar owners before coming up with Pinelands Brewing, a nano he and his homebrewing partner, Luke McCooley, want to get rolling with a German-style wheat brew spiced with coriander and dried lemon peel, a smoked English special bitter and an imperial stout.

Jason Chapman of Hammonton (Atlantic County) says he unsuccessfully made similar pitches to bar owners before coming up with Pinelands Brewing, a nano he and his homebrewing partner, Luke McCooley, want to get rolling with a German-style wheat brew spiced with coriander and dried lemon peel, a smoked English special bitter and an imperial stout.

The brewery's name is an ode to the Pine Barrens and those things associated with it. "I'm from this area. I grew up camping, fishing and canoeing, all the activities that are typical of the Pinelands area," Jason says. "Cranberries are in the plans for brewing. I've brewed some tasty cranberry beers, and being from Hammonton you have to brew with blueberries."

Last winter the two put money down on a building in Egg Harbor City. "It was built for a soda company some years back. It has the high ceilings, a floor drain system already built in, which is a big sticking point for breweries," says Jason, whose day job is a heating and air conditioning technician.

"It was built for a soda company some years back. It has the high ceilings, a floor drain system already built in, which is a big sticking point for breweries," says Jason, whose day job is a heating and air conditioning technician.

"I have the equipment and the experience and recipes to brew 1- to 2-barrel batches. It's just a matter of getting the capital together to get the kegs, the advertising, the intricacies of starting an actual microbrewery."

FOLKS IN THE PHOTOS ... Top to bottom: Jeremy Lees (photo supplied to BSL); (from left) Robert Krill, Chris Henke and Ryan Krill; (from left) Luke McCooley and Jason Chapman.

2 comments:

Thanks for more info on this, doesnt look as hard now

Great article - I've been wanting to start something like this myself, but I'm completely clueless from a legal perspective. Can you give a few pointers about how to go about acquiring the proper licensing??

Post a Comment