It's beginning to look like a stretch run at Kane Brewing in Monmouth County.

It's beginning to look like a stretch run at Kane Brewing in Monmouth County.

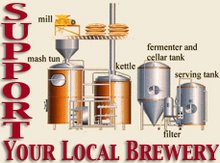

Floor work is finished, and the brewhouse, fermenters, and bright tanks that arrived months ago have been set in place.

Founder Michael Kane expects electrical and plumbing work to be largely finished this week, setting the stage for necessary local inspections and final inspection by the state. The current forecast is for brewing by the end of June (barring any hitches with inspections).

Since late March, when he arrived in Ocean Township to take the job as head brewer at Kane, Clay Brackley has been conducting pilot brews (among other tasks), testing both malts (brands and varieties) and yeast strains, resolving some quality preferences that will be crucial to Kane's inaugural batches of beer (think American IPA) and beyond.

Clay, a Nevada native who homebrewed while he studied forestry in college, came to Kane via a somewhat circuitous path: Nevada (BJ's Restaurant and Brewhouse chain), Alaska (head brewer at Sleeping Lady brewpub in Anchorage) and Pennsylvania (Victory Brewing).

Michael describes Clay's fit, aside from his obvious brewing experience, as something of a shared vision, an understanding of what Kane Brewing should be in New Jersey's craft beer market.

"We were trying to find someone who would fit in well with what we wanted to do ... someone who had the same interest in the style of beer we're going to be making and seemed to really enjoy brewing beer and was really into the craft beer scene and had the energy we're looking for," Michael says.

For his part, Clay says his time in Nevada taught him the nuts and bolts of large-scale beer-making, instilling in him what makes for best practices in a brewery. Alaska, rich in beer culture and ironically a place where you could get craft and import brands unavailable in Reno, was where he began hitting his stride as a brewer. (It also landed him in the winner's circle of the Great Alaska Beer & Barley Wine Festival.) Pennsylvania was a brief layover in his return to the lower 48, and Victory Brewing in Downingtown, Pa., imparted some important lessons from an automated brewery. But at the same time, Clay notes, it separated him from that certain intimacy with the product that a craft brewer experiences.

Clay, who just turned 30 last week, recently took some time to chat and talk about his brewing experiences and his path to New Jersey.

BSL: What got you into brewing?

CB: I started to make beer in college to save money. I liked craft beer from the beginning. When I was younger, I remember tasting my dad's Coors Light or Budweiser and I thought it was terrible. I thought all beer was bad until I got a taste of some Sierra Nevada Pale Ale, some hoppier beers and some English beers.

I liked them, but it's really hard to afford $8.99 or $6.99, $7.99 a six-pack when you're in college and just scraping by. I found out you could spend like 22 bucks on ingredients and make five gallons of beer. Sure, it takes time and effort. I thought it was fun at the time and started doing it and got the brewing bug. It's like people who love to cook. You learn how to do something, you love to do it and you keep doing it.

BSL: And then, perhaps, on grander scales.

CB: I never really thought I would ever be a professional brewer. When I was in college (University of Nevada, Reno) I went for forest and range management. I just thought this is a dream job, this is something that would never happen ... I never knew how I could get into it. I'd even talked to some of the brewpubs, and their brewers had been there for years, and they weren't going anywhere. So I was like, 'I can't work there, that guy's not quitting.'

BSL: But you did get in the door, at BJ's. Talk a little about that first paid gig at a commercial brewery. How did you land the job?

CB: They had a little hiring thing when they first opening the BJs, it was mostly for restaurant people. I went to the restaurant hiring lady, I said, 'Look, I already have a job, I don't need a job ... I really love making beer, I want to learn more about making beer. I want to volunteer to work for the brewery, who do I talk to?' She got me in contact with (brewmaster) Dan Pederson.

At the time I was making pretty decent money; I was actually in the restaurant industry as a sous chef. It was a good job because I didn't have to work a lot of hours. I made good money and it worked well with my class schedule. (Dan) was offering me a Monday through Friday, 40-hour job, which was actually a pay cut at the end of the month when I looked at it. I was like, 'This is going to be a struggle,' but I thought it was an opportunity I couldn't pass up.

About three years into it, I moved from just basically a grunt assistant not really knowing what was going on, to actually running the brewhouse, just like the brewmaster. They were so busy dealing with the paperwork and the corporate stuff – logistics of getting certain beers to certain markets and the taxes. I was just basically doing what they told me to do on the brewhouse.

BSL: What was their capacity?

CB: We did around 27,000 barrels a year. They kept growing and growing. The facility was a 50-barrel brewhouse, 100-barrel fermenters. It was all draft-only, so there was quick turnaround.

BSL: What were some of the beers?

CB: Piranha Pale Ale ... the Brewhouse Blonde was a kölsch. We did Jeremiah Red, which was a high-gravity Scottish/red ale. Tatonka Stout, which is an imperial stout, and then we did some seasonals; we did a hefeweizen ...

BSL: At what point did you get to Alaska?

CB: I was working there (at BJ's), and I had the experience, but the pay scale didn't go up unless you went and became a brewmaster, and there was no opportunity within that company to advance ... I really got tired of scraping by. You can only survive on $9.50 an hour for so long before you're like, 'Why did I go to school?' And student loans were coming due. I was like, 'If I'm going to do this brewing thing, I gotta do it, I can't just stay here. I would have to quit and get another job.' ... So I started looking on ProBrewer.com and saw an opportunity up in Alaska for a head brewer. They offered me a lot better money, also the ability to have creative control, to make a bunch of beer and see what I could do on my own. I just went up there and took over.

BSL: This was a brewpub, right?

CB: Sleeping Lady Brewing Company was the brewery, and the brewpub was called Snow Goose Restaurant (in Anchorage). It's kind of a remote area in Alaska. So they just took homebrewers that had experience. It's not like you can just tap into the local brewing community and find somebody from another state. They were kinda just picking with what they had; so basically they had homebrewers – smart dudes that made good beer – but they really weren't trained on how to operate the systems properly.

BSL: What challenges were you faced with working at a new place?

CB: When I started, I didn't have any training from the previous brewer. I basically started and three days later I was brewing. I saw a lot of things that were kind of jury-rigged, kind of just put together without someone who'd seen it done by professionals before.

For instance, dry-hopping. Normally, at a large production brewery you would dry-hop in your conical fermenter because the cone allows a lot of the hops to drop out, and then you can transfer off of that. They had dry-hopped in a serving tank without a standpipe. They basically took large bags of hops and threw them in the bright tank. This was actually hooked up on their draft lines to send up to the restaurant. I looked at the draft line one day and it was empty – and there's supposed to be 3 or 4 barrels of beer in this tank. One of the big balls of hops had rolled in front of the bottom of the tank and clogged it. There was beer in there that couldn't get out. So I had to open it up, and there was all this beer I had to dump and all these bags of hops I had to throw out. That was just one instance. There were all kinds of things. That's what I did up in Alaska – I just applied the stuff I had learned at BJ's to this brewpub.

BSL: So you tightened up their practices, put them on a better footing as far as brewery management went?

CB: Yeah, I got some decent paperwork going on, started doing (yeast) cell counts on all our beers, got a clean fermenting yeast, we were pitching with the right amount of oxygen, we were keeping everything clean. I don't even know how they sanitized their loop from the heat exchanger to the fermenters. When I got there, I had to rig up some stuff to make it happen until I bought hoses that allowed me to create this loop so you could recirculate hot liquor from the heat exchanger all the way back to the hot liquor tank, so the whole loop is 180 degrees and 100 percent sanitary.

BSL: The kinds of beers that you were making there, what were they?

CB: We had 15 draft lines and seven of those were the standard beers. We had the Gold Rush Golden Ale, which was not even like a kölsch. I considered it like an American golden ale, but very light and dry. Then we had Urban Wilderness Pale Ale, Fish On IPA, Portage Porter, John Henry Oatmeal Stout, Forty-Niner Amber Ale and Old Gander Barleywine.

The other handles I could put on anything that I wanted to. The owner was really, really cool. He just let me brew whatever I wanted to. He was a banker, he made a lot of money, he wanted to have a brewery and he loved beer. His only requirement was anything that I put on, he could randomly show up at any time and he had better like it. Otherwise he was gonna come straight to my office. I made sure I wasn't going nuts, that I wasn't doing anything super-crazy. But I did a lot of fun stuff that was unique and different.

BSL: Such as?

CB: I made a pumpkin beer with real pumpkins. I actually bought sugar pie pumpkins, had to get there at like 4 in the morning to roast ... We brewed an ale with real squash and pumpkin, not just canned pumpkin.

We started a barrel-aging program (with both bourbon and wine barrels) ... I started experimenting with sour beers, but we weren't a packaging brewery so I really wasn't going to put sour beers through my draft lines. So I made only a couple of experimental batches that we were eventually going to hand-bottle just to have, maybe put it in a firkin.

BSL: What was the beer festival scene like up in Alaska, in Anchorage. Can you share your experiences with that?

CB: They don't have a lot of brew festivals in Anchorage. The biggest one of the year is the Great Alaska Beer & Barley Wine Festival. It's held in January, so it's freezing cold outside. It's a perfect time for barleywine, and it's been a thing they've been doing up in Alaska for a long time. Sierra Nevada Bigfoot Barleywine won in '97. A lot of guys have won in that barleywine competition. It's a very well-run competition, as well as a beer festival.

BSL: This is the 2008 competition you entered, right? Going into it, what did you think of your chances?

CB: I knew I had a really good barleywine. I brewed two different barelywines; all of it I just threw down into the barrels.

As soon as I got started and I had time to brew, I brewed barleywine and started it on my Jack Daniel's barrels. I had the barrels, and I knew it was going to take a long time for this beer to be ready. So I had some stuff to play with. And we didn't just take everything out of every barrel and put it in the tank. I took a couple select barrels, we blended those together, and some of the rest of the beer we continued to let rest. And that was our blend. That was our Old Gander Barleywine. It was a little bit unique because of the fact that it had multiple recipes, also differences from the different barrels – the same recipe in two different barrels might be very different. Some more vanilla, some toastier, some a lot more bourbon. We picked them all so it wasn't like over-the-top whiskey taste; one of them was actually a little hoppier, whereas the other one was sweeter. Blending all those beers together I think made a real big difference, and we came out with the first medal that brewery ever won. We got second place overall and we got best of show, or Best in Alaska.

BSL: What were some of the beers you beat?

CB: There was Deschuttes Jubelale ... there was Bigfoot Barleywine, Dogfish Head's Olde School Barleywine, all the Alaska barleywines from Midnight Sun's Arctic Devil to Alaskan Brewing Company's barleywine ... It's a huge, huge, huge haul. Pretty much everyone that has a barleywine gets entered in the competition. There's maybe 50 barleywines that get entered.

BSL: Talk a little about your decision to return to the lower 48 after being in Alaska.

CB: It was fun, and I really liked it up there but the seasonal aspect was getting too much for me. I wanted to be in a place that I was going to want to live for the rest of my life ... I stuck it out, I liked Alaska, but I didn't think it was a place I wanted to spend the rest of my life. So I just kinda looked for a better opportunity, and tried out with Victory for a little bit ...

BSL: And you landed with a start-up beer-maker, Kane Brewing, where you're, once again, the hand that shapes the flavor.

CB: The creative control, I didn't think I would miss it, but I did miss it.